Your student is probably drinking without you knowing, according to survey

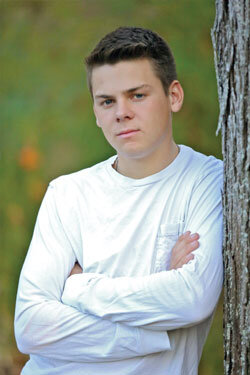

Tyler Grandsko, a recent graduate of Toledo Christian Schools, knows what high school kids do on weekends.

Student Brian Hoeflinger died in a drunken driving accident in February. Photo courtesy Brian and Cindy Hoeflinger.

“They are drinking a lot,” said the blunt 18-year-old.

It isn’t hard to get alcohol.

“It’s all about connections,” he said. “It always leads up to people they know. If someone has a big party, there is always that one person there who has an older brother. You can get it anywhere.”

Some teens even buy an ID from someone who kind of looks like them because getting a fake one costs about $70, he said.

Tyler said teens are drinking at their houses with their parents knowing; they are drinking at their houses without their parents knowing; they are drinking at a friend’s house because their parents told them not to drink; and they are even drinking at school sometimes.

“I have a buddy of mine who would have people over and have bonfires. His parents were upstairs; they were home, but they didn’t know.”

And the so-called “good” kids are doing it, too.

It isn’t just one group of students. It is more than the skaters or the party kids or the “lower half” of the school, Tyler said. It is the athletes, the homecoming queens, the presidents of the class. It is everyone.

Some ways to get drunk fast include vodka shots through the eyes and alcohol-soaked tampons, according to experts. Tyler said getting alcohol directly into the bloodstream is gaining popularity so he has heard of teens injecting vodka into their veins.

Students Kelsi and Kristen Berry said drinking eased after Brian Hoeflinger’s death but has since picked up. Toledo Free Press Photo and cover photo by Joseph Herr

Students Kelsi and Kristen Berry said drinking eased after Brian Hoeflinger’s death but has since picked up. Toledo Free Press Photo and cover photo by Joseph Herr

“I know kids will just put vodka in water bottles to drink in school and on buses to and from school or sporting events. This one is a little different, putting alcohol in cologne spray bottles and spraying it in their mouths during school.”

Drinking usually starts in high school with partying becoming more prominent in the junior and senior years.

Some students drink to be cool; some do it just to get drunk. Usually it’s a combination of both, Tyler said. Beer and liquor are equally popular.

The first — and only time — that Tyler got falling-down drunk he did it as a way to just kick back and relax with his buddies.

He drank 12 Bud Lights and a full grape Four Loko.

“I wanted to forget about everything that was going on and just have a good time,” he said.

“Because the alcohol was there, I drank it.”

At the time, Tyler was a sophomore at Toledo Christian, a school that has minimal underage drinking, he said.

“I moved away from Anthony Wayne in fifth grade. I came back in eighth grade and then by freshman year, there were people drinking and smoking weed.”

While some people might think underage drinking is an urban problem, Tyler said it is sometimes worse “in the boonies.”

“I walked upstairs and I was so out of it. I thought this one girl was upstairs, but it was [my friend’s] mom,” he said. “I tripped and fell down the stairs. She knew I was drunk and she told my parents about it.”

Tyler got in trouble. His family was moving, so as a punishment he was grounded and couldn’t visit any of his friends to say goodbye.

From that day, he made a decision that he would not drink for the rest of his high school years. He continues to honor that pledge as a freshman at Bowling Green State University.

“It isn’t worth it to get in trouble. The feeling is terrible. I don’t want to throw up every night or not be able to open my eyes until noon,” he said. “Be your own person; set your ground rules for how you want to live and don’t let anyone influence you. That is how I have been living my life since that day, ever since I got into trouble.”

What is even more amazing is he made this socially unpopular decision before his friend Brian Hoeflinger died in a drunken driving accident.

Wake-up call

A makeshift memorial at the site where Brian Hoeflinger died in February. Toledo Free press photo by Sarah Ottney

A makeshift memorial at the site where Brian Hoeflinger died in February. Toledo Free press photo by Sarah Ottney

Kelsi Berry was in charge of setting up for a dance at Ottawa Hills High School on the morning of Feb. 2.

“Everyone was talking about how we can’t have the dance anymore. I said, ‘What happened?’”

Someone said, “Brian Hoeflinger has passed away.”

“I didn’t know what to do; none of us knew what to do,” Kelsi said. “I walked into my mom and dad’s room and told my mom. She was in shock. She used to take him to the dentist.”

The close-knit community of Ottawa Hills would soon learn that the 18-year-old senior had been drinking at a party the night before. He was southbound on Edgehill Road and his vehicle went off the side of the street, struck a tree and caught on fire. His blood alcohol level was .15.

Kelsi, a sophomore, said she did not associate drinking with Brian. She can usually tell who is a drinker, she said, and she didn’t think Brian hung with that crowd.

“You would never think of him drinking or anything. It was strange and hard to grasp,” she said.

But more teens drink than those who don’t, experts say. If you think your child drinks, he or she does. If you think your child doesn’t drink, he or she probably does. The statistics are compelling.

Nearly 30 percent of adolescents report drinking by eighth grade, and 54 percent report being drunk at least once by 12th grade, according to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Amy Barrett, director of AWAKE Community Coalition, an Anthony Wayne-based coalition dedicated to preventing substance abuse, said if parents think underage drinking is only a Toledo problem, they are taking a “head-in-the-sand approach.”

“We have found that it is everyone,” Barrett said.

In 2011, the results from a local health assessment mirrored national trends. The survey indicated that 54 percent of Lucas County youth in grades seven through 12 had consumed at least one drink in their life. Thirty-seven percent of those seventh- through 12th-graders who drank took their first drink at 12 years old or younger.

The survey also revealed that more than half of the seventh- through 12th-graders who reported drinking in the past 30 days participated in binge drinking, while 6 percent of all youth drivers had driven in the past month after they had been drinking.

Tyler was at a basketball game when his dad called to tell him about Brian’s car accident.

“Dude, your buddy just died,” his dad said.

“Who are you talking about?” Tyler asked.

“Brian.”

“I was like, ‘No way.’ I had just played golf with him two weeks ago. There is no way that just happened. It was kind of a shocking-type of feeling. I was just sitting with my girlfriend and buddies. You aren’t aware of anything. I just flashed back to memories.”

Tyler knew Brian through their golf rivalry. Tyler played for Toledo Christian; Brian played for Ottawa Hills. Before his senior year at Ottawa Hills, Brian had attended St. John’s Jesuit High School.

“Once he came to Ottawa Hills, there was a big rivalry between us,” Tyler said. “Me and him had the same drive when it came to athletics. We always loved to win and do our best, and our best was never good enough.”

Tyler said he didn’t know Brian was a drinker. While most students seem to get alcohol through an older sibling, Brian’s alcohol came from a liquor store the night he died. The clerk who sold it to him has been charged.

“When alcohol was involved and in the headlines and stuff, I thought he had gotten hit by a drunken driver,” Tyler said.

Does Brian matter?

After Brian’s death, his parents, Brian and Cindy Hoeflinger, began a crusade. They want to ignite a frank discussion about underage drinking.

“We wanted to get it out in the open and not be ashamed of it,” his dad said.

Brian was a good boy — but even good boys like to experiment.

“Parents need to talk about it; they need to start a line of conversation,” Brian’s dad said. “Millions of parents don’t think of talking about it because they don’t think their kids are doing it.”

Bottom line: Err on the side that assumes they are drinking.

The Hoeflingers founded “Brian Matters” as a way to continue the conversation at local schools and offer students an opportunity to take a pledge against underage drinking.

Tyler supports the Hoeflingers’ mission. Initially, “Brian dying was a huge eye-opener,” he said. But it didn’t last long.

Within two weeks, some teens had gone back to their old ways. Some students even removed their pledges from the wall, according to a sophomore at Ottawa Hills who didn’t want his name used.

The 16-year-old said many of his friends drink, which puts him in a tough spot because he doesn’t want to lose all of his friends. Although it is mostly a weekend thing, people will even leave for lunch to drink.

Tyler said it is frustrating.

“Because it didn’t happen to them, they can keep doing it. They think it is fun to get trashed. I don’t understand how you can do all that stuff and then have a friend from your school, who you said you were so close to, die.”

Kelsi said when the Hoeflingers talked to their school about taking the pledge, some seniors got up and left. Some took it — and broke it.

“Why take it and not follow it? That is making a bad promise to Brian and his parents,” Kelsi said.

Her sister, Kristen Berry, a junior, said the drinking decreased for a week after Brian died. Then, everyone went back to partying. Her observation is that they care about Brian and his family, but they continue to drink because of the pain of his death.

“I just hang out with kids who don’t like to do that stuff. I know a couple of people who do. I know that isn’t something I want to do because of my morals and values. I don’t want to drink; I don’t see any reason to.”

The elder Hoeflinger said he knows some teens only take the pledge because everyone else is doing it.

“I don’t expect everyone to change. We are just out to change who we can. We are trying to give them a different way of thinking,” he said.

“If you don’t have any intention of following the pledge, don’t sign it. If you don’t think you can — don’t do it.”

Why still do it?

The reasons for drinking are individual. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, youth often view drinking as a rite of passage and want to see who can be the bigger rebel. They like the feeling of getting drunk and they like that it makes them feel as if they can talk to anyone even though they are normally socially awkward. Sometimes drinking leads to drugs, but drinking is the first risk that many students take — that or marijuana.

Andrea Loch, a ProMedica St. Luke’s substance abuse counselor for Anthony Wayne and Maumee schools, said underage drinking isn’t a new problem, but parents are sometimes oblivious. They operate under the “Don’t Ask” system and “kids are obviously not going to tell them,” said Loch, a mother of four.

The first sip usually comes in junior high school or freshman year. The excess drinking becomes popular as upperclassmen. Wine coolers are attractive to younger drinkers who eventually discover beer and liquor.

Brian’s sister, Christie Hoeflinger, said kids in seventh grade joke about drinking, but she knows it will eventually be a reality.

“They are going to drink and be like, ‘Oh, come on, it is just one.’”

But she knows it won’t just be one. She believes her brother only drank a couple of times — and he died.

“I miss his silliness and goofiness. It annoyed me at the time, but he always used to playfully slap the dog and then he would sometimes slap me and say, ‘I thought you were Nautica.’”

Until recently, the dog would still wait for Brian to come home, she said.

Loch said teens drink to feel grown-up, to be bold and to rebel. Drinking is especially dangerous for teens because their brains aren’t fully developed and it could further impair their already-weaker judgment, she said.

Ronald Birchfield III, who attended St. John’s with Brian, said his classmates didn’t care about the risks. Some began drinking as early as freshman year. By the time he was a sophomore, teens had parties when their parents were out of town.

“I am not sure why they drink. I think they feel the need to have something in their system to not have as much self-control,” said the premed student at The Ohio State University.

Ron said he knew that Brian drank, but he didn’t know to what extent. Ron attended parties, but he didn’t feel pressured to drink.

“Losing one of my best friends, practically my brother, I don’t even find it appealing,” Ron said. “I am definitely not average. I don’t drink and I am not just saying that.”

Kelsi said the sophomores at Ottawa Hills drink to fit in with the upperclassmen.

“Someone in my grade had a birthday party and some of my friends went to it. There were some girls I know who didn’t drink anything, but they pretended to be drunk so upperclassmen would talk to them.”

Kristen said some students will drink a little and others will binge.

“Last year, a lot of the upperclassmen would get pretty drunk. They would show up to functions like dances. It sometimes gets to the point where you can’t even tell if they are drunk because they do it so often they have gotten good at hiding it.”

She fears asking the wrong person for a ride.

Most teens don’t drink and drive, though, she said. They spend the night; they walk. They try to be responsible when it comes to that.

But not always … Brian left.

“You could not only hurt yourself, you could hurt your friends. If Brian had someone in the car with him that would have been terrible,” Kristen said.

One reason some Ottawa Hills teens keep drinking is because Brian died.

“They don’t think it will happen to them. It has already happened; it won’t happen again,” Kristen said.

Don’t be naive

Talking about underage drinking is the first step to curbing it, according to Hoeflinger. Parents and school administrators need to work together.

Jeff Gagle, superintendent of Toledo Christian, said he would be a fool to think none of his students drink.

The reason the problem is less pervasive at Toledo Christian is because the school, parents and students are a team.

“We do a lot with student leadership,” he said. “They police our own culture. There is positive peer pressure.”

Gagle said when upperclassmen plan the homecoming dances and participate in activities without drinking it impresses upon the younger students.

“Use the students, give them opportunities so they have to stand up to conflict; they have to stand up against the norm,” Gagle said. “Our parents in our school, we refer to them as partners. Sometimes we have had parenting seminars. You have to make the parents aware of what is going on.”

Gagle said public awareness of underage drinking, and drinking in general, is helping. Law enforcement takes drunken driving more seriously than ever.

He believes Brian’s death has made an impact.

“Young people at that age think they are indestructible. It was a message,” Gagle said.

Kevin Miller, Ottawa Hills superintendent, said losing a student like Brian affects everyone.

“There is an empty desk where a wonderful, vibrant student had been sitting,” he said.

Miller said he is sure that Brian’s death made some students stop drinking or, hopefully, never start. However, that is hard to prove.

“We will never know, though, because those kids aren’t lying in a ditch.”

Statistically, the longtime educator can’t say more students are drinking, but it seems like teens are more bold and brazen than they were 20 years ago.

Even before Brian’s death, Ottawa Hills addressed underage drinking and drug use, beginning with D.A.R.E. in sixth grade. The high school is home to a Challenge Crew, which promotes positives changes in the community.

After Brian’s death, though, the discussion in Ottawa Hills has moved to a “village solution,” not a “school solution,” Miller said.

“We do our best to influence kids, but no one has a greater influence than parents. Brian’s death has made parents acutely aware of their role.”

Loch said parents need to set clear rules, follow through on consequences and talk to their kids about alcohol. Too many parents think because the student might have heard about the dangers of drinking in school they don’t need to talk about it again, she said.

That is dead wrong.

“Hands-down, parents are the single biggest influence, while schools provide additional support,” Barrett said. “Teens and kids in general rely on the adults in their lives to help them make those tough decisions and provide them with good advice.”

But kids won’t ask for this advice, she said.

“Initiate it. It is never too early to start talking about it.”

For example, cigarettes are now considered “bad, bad, bad,” she said. It is time to frame underage drinking in the same manner.

“Check on them. Be vigilant. Ask the questions. Don’t be afraid to check up on things and make that phone call,” Barrett said. “Have kids leave things at the door. Years and years ago, it was beer. Now it is vodka in Gatorade, vodka in the water bottle. Chances are it is happening right under your nose.”

Miller said to remember it could be a kid who otherwise seems like a model teenager.

“I have seen great, great kids make a bad choice. When they make a bad choice, you hope they get caught and learn and move on,” Miller said.

“Brian didn’t get that opportunity. It cost him his life.”

Originally written for the Toledo Free Press